To summarize the points I’m trying to make here is, 1) we all wrestle with feelings of inferiority at times, 2) social mores demand that we only reveal our successes, never our failures, and 3) one of the best ways to combat this universal social ill is honesty. We all fail in 80% of our endeavors, yet we hide those failures due to the social shunning of failures. If we were all honest about our failures, it would create a much healthier culture, so I assume. Coming of age in the 1960s and 70s was difficult. But these days, with social media, it must be atrocious for middle schoolers and teens. I just can’t imagine. Social media is a place where no one can show weaknesses.

In 1990, as I’ve shared before, I decided to pursue truth as best as I can and this truth is on a philosophical level as well as a pyschological honesty. This is how this practical topic of social behavior intersects with my “higher-brow” endeavors into the loss of truth in the late-postmodern social climate.

In 1975 I spent the summer in Knoxville, Tennessee as I was part of a “summer training program,” which was The Navigators discipleship program for college students. The Navigators is a very serious evangelical group that puts an emphasis on discipleship. Another guy, Jim, was part of the same training program and since I had a car and he didn’t, he caught rides with me. I had just met Jim, who recently left the Army to become a sudent at the University of Tennessee. In the army, he was a Ranger (similar to today’s Navy Seals) . He had the typical macho persona. He caught a ride with me to find a church to attend while we were in Knoxville. We attended a small conservative church on a small hill just outside of town. The sunday school teacher that morning was a man in his forties named Tom, an engineer from TVA (Tennessee Valley Authority). Tom, at a moment of great vulnerability, became teary-eyed and shared with the group that there was a crisis in his marriage and asked us to pray for him. Once he regained his composure, he then led the class. I was impressed with his humility and honesty. Some of you may be thinking that was inappropriate to share such personal information in a pubic forum, but that’s my point. On the way out of that sunday school class, my new friend Jim commented in an angry tone, “What a looser! I’m never coming back to this church.” This reflects how our culture often shuns weakness and failures, although mistakes and weakness accents our real lives at every turn.

There are certain places within our culture where social mores demand that we hide our weaknesses more than others. This is especially true In professional circles, especialy in high intensity work places. Denise’s favorite TV series is Suits. I’ve watched it a few times and the workplace is cutthroat, dog eat dog if you will. If you showed weakness there, it would not go well for you. The military is another such culture (and I witnessed it first hand when I was in the Airforce). I suspect in all those places people have a well-hidden place of self-doubt.

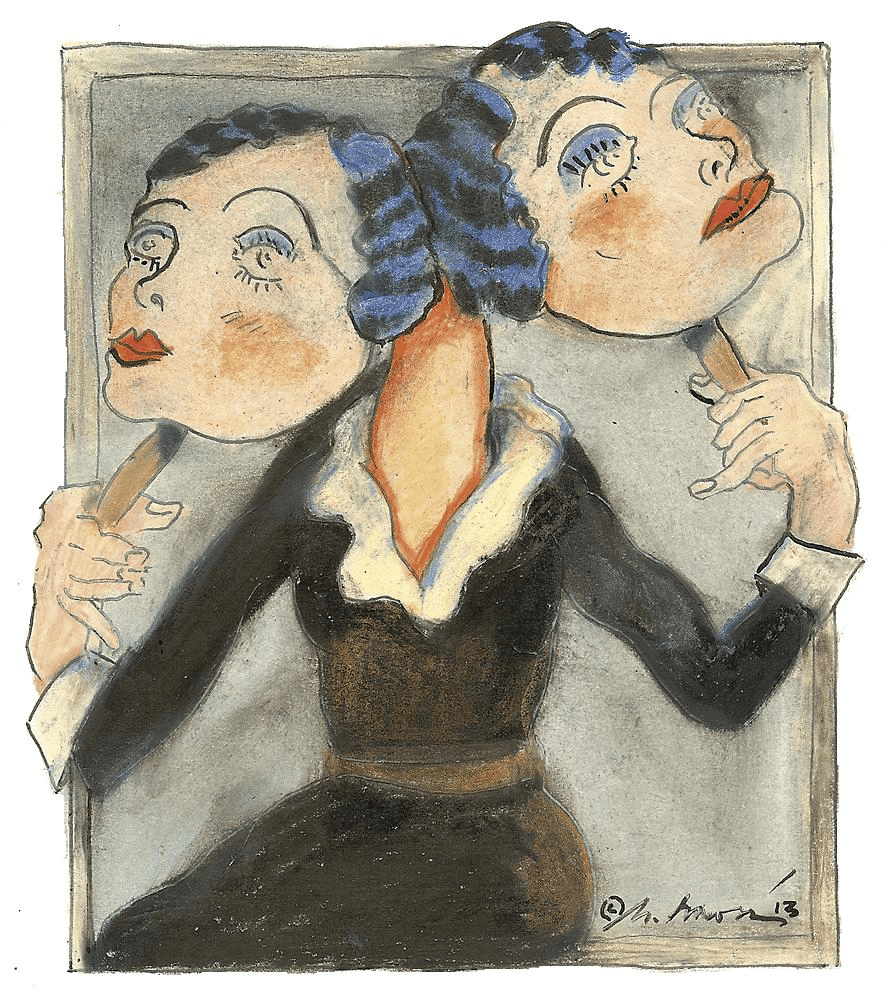

Some religious circles have their own subculture where there is a wholesale denial of imperfections. I have earned the right to criticize American evangelicalism because it took 28 years from my life. I suspect that there are few places more pretentious than an evangelical chruch on Sunday morning, save maybe a politician in front of a hot camera. I call the Sunday mornging service in the evantelical world, the “beauty pagent.” It is where you not only look your best, ties included, but you wear a plastic smile and share only your great success as a person, a parent, husband, or so-called spiritual person. That’s why Jim (mentioned above) was so shocked at Tom’s candidness. This attitude supports the myth that we are just spiritual beings (no brain or brain function) and we can be “good” by choice. In that fantasy land behind the looking glass, there is no fundamental human tendencies to make mistakes. Mistakes in that world are all a moral problem, over which good people have final control. Within that context, our insecurities are buried deeper and deeper.

Speaking of religion, it is a double-edged sword when it comes to feelings of inadequacy. If you take it at its basic philosophical assertion, we are created by a loving being (in the case of Christianity) and made this being’s image, that is profoundly helpful in assigning value to ourselves because that value is intrinsic. Unmerited. However, many religions have pathological asertions as part of their culture that makes our feelings of low-self esteem much worse. It is a theme within some parts of the Christian culture as well as within Islam, that we are all filthy wretches, so nasty that God can’t even look at us unless (in the case of Christianity) it through the filter Jesus’ perfection. That cultural tenet also requires each individual to take responsibility for the torture and murder of Christ, an unbearable burden. I believe that was the purpose of Mel Gibson’s movie, The Passion of Christ. Within that culture, you cannot take credit for any success. If a singer worked tirelessly on her music since she was six years, then does a brilliant performance in a church, she is obligated, when complimented, that she takes no credit, only God. That makes no sense, and I think God applauds her hard work and is surely comfortable with her taking credit.

Atheism too is a double-edged sword when it comes to appriasing one’s self-worth. On a philosopical and logical level, the notion that you are a product of an accidental, impersonal process, cannot impart meaning or value. My atheists friends would say that they gather a sense of self-worth and meaning through an existential process. But using classical logic, that is but a paper tiger. On a positive note, the atheist can avoid the negative tenets, mentioned above, of some religious groups.

I’m going to close this whole topic by describing my own struggles with a low-self esteem. I will do that in the final installment of this series. But I do want to state clearly now why I’m doing this. The pyschologists in the series of Hidden Brain challenged us to be more honest about our struggles. Each of them shared painfully personal stories of their own struggles. Because talking of our failures is so unusual in this culture, invariably, when I share honestly someone writes me, with good intentions I suspose, to rebuke me, to direct me to help, or say other things that imply that I’m an outlier. That no other person–who has their shit together–would have these struggles. But that’s my point. To show that my struggles are the rule, not the exception. It will not be me “crying for help” or seeking advice. My intent is to help others feel better about their own struggles.

Mike

Leave a comment